Intersectionality and Disability: A Conversation with Reshawna Chapple, PhD, LCSW

Reshawna Chapple, PhD, LCSW is an associate professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Central Florida.

You are a codirector for the AHEAD-DC RRTC (Advancing Health Equity for Adults with Disabilities from Diverse Communities Rehabilitation Research and Training Center). What do you see as your main priorities within this research grant?

Reshawna Chapple, PhD, LCSW (She, Her, Hers): I oversee areas that have to do with training. I see my main priority within the research grant as making sure that all projects in all areas are proactive where it comes to being inclusive, being culturally responsive, and thinking about issues of equity and intersectionality. My focus in training is helping to bring, first, the perspective of counseling disciplines like mine [social work] into the fold and helping where medical students and other individuals are being trained to look at individuals with disabilities broadly.

You are an expert in social justice, and a lot of your work revolves around the concept of intersectionality. Can you define intersectionality for us?

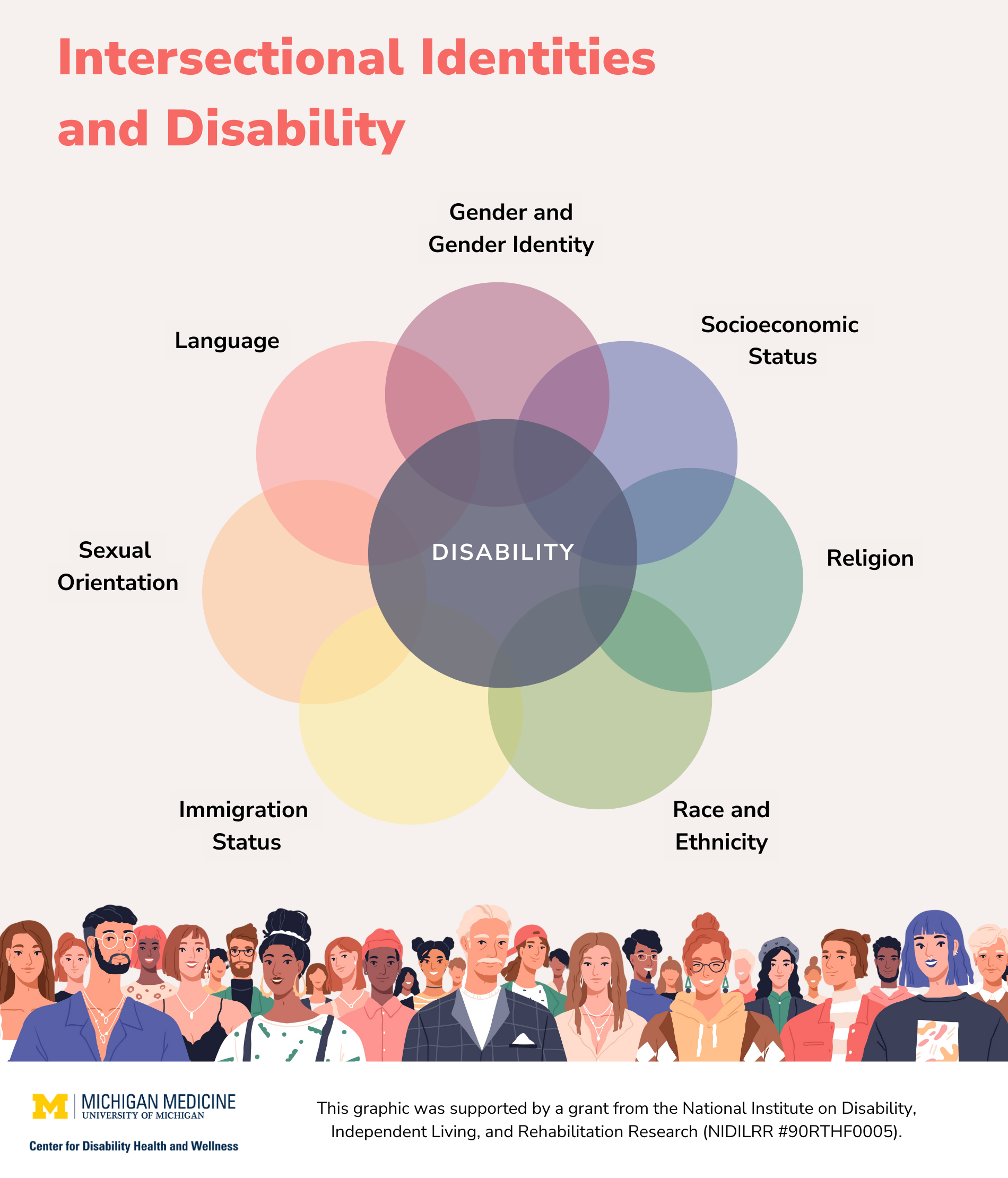

Dr. Chapple: A simple definition for intersectionality is the idea that people's identities are complex and fluid, and they all intersect at some point in their life, depending on their social situation.

More broadly, intersectionality explores issues of how race, class, gender, and other marginalized identities are critically related to produce a structure of oppression that is often experienced by marginalized peoples. Intersectionality is not just adding up the discrimination related to each marginalized identity; it seeks to understand how each identity shapes an individual—a whole individual with interacting characteristics, such as race, gender, disability, age, and/or sexuality. Intersectionality works on this individual level, but also on a societal/structural level, revealing the way systems of power develop and maintain inequalities and social injustice. Kimberlé Crenshaw first introduced this term to indicate ways in which Black women were discriminated against or marginalized due to their intersecting identities as Black and women. Although Crenshaw was the first scholar to “name” the concept, the idea of analyzing race, gender, and class identities together has existed for over a century. Anna J. Cooper, Mary Church Terrell, and W. E. B. Du Bois have implicitly mentioned the concept of intersectionality.

With physicians increasingly looking to engage in patient-centered care, intersectionality fits very well in a clinical context.

Dr. Chapple: Yes, as social workers, we are constantly focusing on the individual in their environment, and we are trying to meet the patient where they are. When we start thinking about intersectionality in any context—and I particularly focus on institutions, educational facilities, and medical facilities—we need to focus on those parts of an individual’s identity that would limit access. But, at the same time, when we think about intersectionality, it is not meant to be a debilitating term, and we do not want to look at it as just a “measurement.” We want to look at the term for professionals to say, “Here are some things that may affect the individual. Here are some things that we may need to consider.” We cannot look at intersectionality after the fact. We do not want to be in a situation in which, for example, we did not consider that a person could not afford their medication, which is why they are back in the emergency room. What intersectionality does, especially in a clinical context, is that it helps us to look at each of those areas of their identity that may be problematic to gaining access or them being able to achieve health equity.

How can we apply the concept of intersectionality specifically to disability?

Dr. Chapple: When applying the concept of intersectionality to disability it's important to recognize that not all individuals with a disability are the same. We want to broaden our concept of disability from believing that all individuals with a disability are homogeneous. With intersectionality we remove all preconceived notions that an individual who uses a wheelchair is a heterosexual cisgender Christian white male from a middle-class background. When thinking about disability it is important to consider that individuals living with disability can come from various racial and ethnic backgrounds, they can practice a variety of religions, they can be members of the LBGTQ community, they can come from various social economic backgrounds, and they can also have multiple disabilities etc. Most practitioners are not trained to consider disability in their practice, let alone consider the additional identity categories that can intersect with disability. It is important to consider that even though you may have interacted with or worked with someone with a disability the next person you meet with the same disability may not have the same preferences. Consider each person as a unique individual. It is okay to ask them about their preferences and not to assume anything about their care.

What would you say to people who are unsure how to integrate intersectionality into their work or their research?

Dr. Chapple: The main thing is to not be afraid of it. It is hard for people, especially experts, to step into a situation in which they are not the expert. It makes people feel extremely uncomfortable, and it generates a lot of anxiety. So, just understand that you may not get it, and it may not come naturally to you, but it is fine. Just keep working at it. Do a little bit of research. In terms of your work in the community, you can start by looking at the people with whom you may come into contact. Try to remove that tunnel vision and understand that people are complex. Ask questions. Listen. This is not limited to intersectionality. It is everything about helping that person be successful and helping them as a clinical partner to have the best health care possible. Once you start asking questions you have opened the door for them to let you know their priorities.

What is next for your work with the AHEAD-DC RRTC?

Dr. Chapple: I am hoping that we can start thinking past foundational pieces [like this one on intersectionality] and move to a place in which we are constantly applying it. So, I would like to have trainings and resources available that people can use. For instance, we are developing an intersectionality checklist, which will help future AHEAD-DC RRTC trainers and speakers integrate concepts of intersectionality within their presentations. I am truly fortunate to work with a very diverse group of people at the University of Central Florida, and in my daily work I am able to see how intersectionality works in practice.

Further Reading:

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139-167. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8 /

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Nash, J. C. (2008). Re-thinking intersectionality. Feminist Review, 89, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.2008.4